Malone-Bey v. Mississippi State Board of Health

Recently, the case of Malone-Bey v. Mississippi State Board of Health (2025) brought to light the potential tensions that can be seen between one's expression of their religious identity and board-approved government documentation. This case raises key constitutional questions about religious free exercise and equal protection under the law, presenting an interesting intersection of the First and Fourteenth Amendments and challenging us to consider the limits of religious accommodations in official state records.

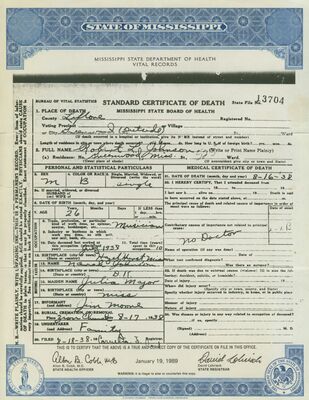

Kent Malone-Bey, a self-identified Moorish American, petitioned the Mississippi State Board of Health to amend his Certificate of Live Birth to reflect his racial identity as “white: Asiatic/Moor.” Malone-Bey, representing himself in court, filed his petition in the Lauderdale County Chancery Court, arguing that the Board’s refusal to modify his birth certificate violated his rights to religious free exercise, due process, and equal protection. He asserted that the inability to have his religiously significant racial identity recognized on his birth certificate impeded his full expression of identity and faith, placing an undue burden on his religious beliefs. However, both the chancery court and the Mississippi Court of Appeals rejected these claims, ruling that the state had no obligation to alter its records to accommodate an individual's religious identity preferences, asserting that birth certificates in the state do not designate race, nationality, or religion of any child, and therefore, no religions discrimination had taken place.

Kent Malone-Bey, a self-identified Moorish American, petitioned the Mississippi State Board of Health to amend his Certificate of Live Birth to reflect his racial identity as “white: Asiatic/Moor.” Malone-Bey, representing himself in court, filed his petition in the Lauderdale County Chancery Court, arguing that the Board’s refusal to modify his birth certificate violated his rights to religious free exercise, due process, and equal protection. He asserted that the inability to have his religiously significant racial identity recognized on his birth certificate impeded his full expression of identity and faith, placing an undue burden on his religious beliefs. However, both the chancery court and the Mississippi Court of Appeals rejected these claims, ruling that the state had no obligation to alter its records to accommodate an individual's religious identity preferences, asserting that birth certificates in the state do not designate race, nationality, or religion of any child, and therefore, no religions discrimination had taken place.

The court's opinion, delivered by Judge Wilson, emphasized that Mississippi’s birth certificates do not include racial or religious identifiers for anyone. Therefore, the state was not treating Malone-Bey differently from others, nor was it discriminating against him based on religion. The court added that neither state law nor constitutional provisions require the government to adjust its internal records to align with an individual’s religious beliefs - in so far as it is applied equally to all.

Constitutional Issues

This case primarily engages with the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Free Exercise of Religion: Malone-Bey’s argument centered around the idea that because he was unable to fully reflect his religious identity on his birth certificate, his right to free exercise was restricted. The Court, in response, relied on Bowen v. Roy (1986), a Supreme Court case in which the government’s use of a Social Security number for a Native American child was contested for religious reasons. The Court (in Bowen) ruled that the Free Exercise Clause does not require the government to alter its internal processes to align with an individual's religious beliefs. Like in Malone-Bey’s case, the court determined that Mississippi’s decision not to amend his birth certificate did not burden his religious practice - instead, it only upheld a neutral, generally and equally applicable policy.

Equal Protection Clause: Malone-Bey claimed that the state’s refusal to amend his birth certificate amounted to religious discrimination. However, the Equal Protection Clause requires proof that the government intentionally treats a group differently without justification. Since Mississippi’s birth certificates exclude racial and religious designations for all citizens, the court found no that there was no discrimination occurring. The state was simply applying a uniform policy, not targeting or burdening a specific religious group like Moorish Americans.

Analysis and Implications

As seen very early on in Reynold v. United States (1897), religious beliefs are to be protected under the Constitution, but religious conduct can still be regulated by general laws. This is the scenario I believe Malone-Bey finds himself in.

His case parallels previous Supreme Court rulings on neutral and generally applicable laws that incidentally burden religious exercise. One case discussed in class was Braunfeld v. Brown (1961), where a group of Orthodox Jewish merchants challenged a Pennsylvania Sunday Closing Law, which required most businesses to close on Sundays. Those who observed the Jewish Sabbath on Saturday, argued that the law placed them at an economic disadvantage by forcing them to close their stores two days a week - once for religious observance and once due to state law. They contended that this violated their First Amendment right to the free exercise of religion by imposing a government-mandated burden on their economic livelihood. The court ruled in a 5-4 decision (very close) that the law was constitutional, and set the precedent that laws can incidentally burden religious practice, insofar as they do not actively target any particular religious group and have a legitimate secular purpose - which in this case was to provide a uniform day of rest for workers. In Braunfeld, the Court found that the law did not force Jewish business owners to violate their faith, only made practicing it more difficult.

Additionally, the case of McGowan v. Maryland (1961) also supported the idea that the government may enact laws that incidentally align with religious practices if their primary intent is secular.

Another case to mention and that I find important to address was the case of Sherbert v. Verner (1963), where a Seventh-day Adventist was denied unemployment benefits for refusing to work on Saturdays. The Supreme Court ruled in her favor and weakened the court's decision in both Braunfeld v. Brown (1961) and McGowan v. Maryland (1961). This case strengthened religious liberty and led to the establishment of the Sherbert Test, which strengthened protections under the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Under the Sherbert test, laws that place a “substantial” burden on religious practice must be backed by a compelling government interest and use the least restrictive means. So what wins out in the case of Malone-Bey?

In the case of Malone-Bey, Mississippi’s birth certificate policy applies to all individuals equally and serves the secular purpose of maintaining uniform state records, making Malone-Bey’s Free Exercise claim weak under this precedent. Mississippi’s birth certificate policy may incidentally affect Malone-Bey’s religious identity, but its primary purpose is without a doubt secular - ensuring consistency in government documentation.

Additionally, the strict scrutiny required under the Sherbert test seems to fall short here as well. Unlike Sherbet, where the denial of unemployment benefits explicitly punished an individual for their religious observance, Mississippi’s refusal to modify Malone-Bey’s birth certificate does not single him out - it applies to everyone in the state. The burden on his religious practice (which would be a minimal form of practice compared to active worship, etc) is incidental and not substantial enough to warrant strict scrutiny in my opinion.

Tying it back to Bowen v. Roy (1986), the Free Exercise Clause cannot require the government to alter its internal practices to reflect the religious conviction of an individual. Just as “the government may not insist that appellees engage in any set form of religious observance, so appellees may not demand that the government join in their chosen religious practices… The Free Exercise Clause is written in terms of what the government cannot do to the individual, not in terms of what the individual can extract from the government.”

So in the case of Malone-Bey, the Mississippi State Board of Health’s policy is neutral, generally applicable, and justified by a legitimate government interest. I am not convinced that his Free Exercise restriction is unconstitutional. I believe it is merely an incidental burden that he faces due to the secular aim of ensuring consistent and efficient governmental documentation, and that the state is under no obligation to tailor its records to his religious preferences.

If Malone-Bey’s request was accepted, it would open the door to countless individualized religious identity claims, and potentially lead not only to complications and inconsistencies in official documentation, but more arguments to be made about what individuals can demand from the government with regards to religious observance and accommodation. By affirming the state’s authority and denying his request, long standing precedents are reinforced that restrict the government from being compelled to accommodate every religiously based identity claim.

3 comments:

If the birth certificate is standardized for everyone and only includes information necessary for government identification and infrastructure, it seems unnecessary to include another category for the sake of one person. They are not forbidding anyone from identifying as Moorish American, they just aren't going to be responsible for labelling anyone in that particular way. Birth certificates are assigned at birth, when it would not make any particular sense to assign a newborn a religion. Birth certificates are meant to record someone's age, identity, and citizenship, anything else is secondary and unnecessary for the original purpose of the certificate.

Religion is not defined by what one piece of paper says. If one does not have their religion on their birth certificate, it does not mean that they cannot freely exercise their religion. The primary objective of a birth certificate is to validate ones citizenship and to be used as a document of identification. As Hannah mentioned, birth certificates are standardized and should not be altered because of one person. Furthermore, I agree with Hannah that not including "Moorish American" does not prohibit one from identifying as Moorish American.

A birth certificate is meant to prove a person's age and that they are a real person. Religion is not required on the birth certificate. A lot of times, peoples sexual orientation is not on their birth certificates, even though that is a huge part of peoples lives. What a person's birth certificate says does not really prevent people from practicing religion nor does it really prevent people from what they identify as.

Post a Comment